Saltwater Ich, also known as Marine Ich, Marine White Spot Disease, is caused by the parasite Cryptocaryon irritans. The term “Ich” or “Ick” is very likely a generic carry-over from the freshwater parasite Ichthyophthiriius. Since both parasites cause white spots on the fish, the disease is universally called Ich or Ick, even though they are different parasites.

A saltwater ich fish outbreak in a marine or reef aquarium is a serious matter. In aquariums and aquaculture environments, fish loss due to an ick outbreak can be very high. Let’s take a closer look at this parasite and learn how to avoid it and if necessary, treat a marine ich outbreak.

Get Your Free Downloadable Reference Chart

I created a chart summary of the methods covered in this post that you can have as a FREE downloadable chart. No strings attached. You don’t even have to sign up for the SaltwaterAquariumBlog Newsletter, even though you’re going to want to. It’s literally just a link to the file I have on my Google Drive. You don’t need to share your info with me, all you need is a Google account to sign in to Google.

here is a link to a free download

Dealing with Ich

Are you dealing with Ich right now? It’s frustrating. You’re not alone. Here’s a video from someone who had to basically tear down their reefs. I’ve been there before too but didn’t video it. Ugh.

What Does Saltwater Ich Look Like?

The cryptocaryon parasites are microscopic, which means you can’t really see them with the naked eye. As aquarists, what we notice first are the symptoms of the parasitic infestation on our saltwater fish, which typically includes: ragged fins, scratching behavior (the fish scratching itself erratically) on rocks or sand, and of course the hallmark white spots or nodules on the gills, fins, and body of the fish.

But just because you don’t see white spots on a fish’s fins or the body doesn’t mean that the fish is not infested with saltwater ich. Sometimes the ich parasites infest primarily in the gills, showing no white spots or other outward symptoms, so it might be worth trusting your gut instincts if you are pretty sure the fish is sick, based on your observation of their behavior.

Marine Ich: Know Your Enemy!

Before entering a battle, it is important to know who or what you are up against. It is the same way with fish diseases. In order to understand how you have to fight marine ich, it is helpful to take a moment to understand the life cycle of ich.

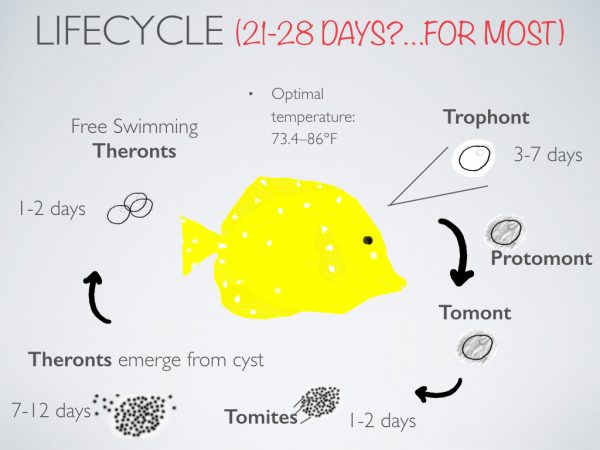

Marine ich has a complex multi-step life cycle.

- The feeding or trophont stage is where the parasites are swimming around under the skin and gills of the fish. The parasites eat cells and fluids, damaging tissues and leaving the fish in a weakened state. Here is where you may see the white spots and other outward symptoms. Ich treatments generally do not affect the trophonts because they are protected under the skin of the fish.

- Once the Marine Ich Trophonts are fattened up, they leave the fish as a protomont.

- Protomonts lose their ability to swim, fall to the bottom of the tank and in a few hours become a tomont. The parasite becomes a hardened cyst, like an ich egg, waiting to hatch. The tomont is a ticking time bomb full of nasty little parasites. What was once a single ich parasite, now divides, again and again, storing up hundreds of new parasites called tomites.

- After a number of days or even weeks, the cyst opens up and the infective parasites are released as free-swimming theronts, seeking to attack your fish. This is really the primary stage that these medications are effective against the parasites. The theronts have about six hours to find a fish and burrow into the skin, becoming a trophont. Then the cycle begins again. Depending on the severity of the outbreak, an aquarium or shop full of marine fish can be wiped out due to the reoccurring nature of the parasite life cycle.

Preventing and Treating Marine White Spot Disease

A lot has been written about saltwater ich treatment, one of the most important and most common challenges in the saltwater aquarium hobby.

Articles on the topic, including those I’ve written in the past, are often littered with cliches like, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” because once the parasite gets in your tank, it is extremely difficult to get rid of.

The traditional advice is to quarantine all of your new arrivals for 28-30 healthy, symptom-free days before adding them to your display tank, to prevent the transfer of this parasite into your display.

But the traditional advice will not keep your tank safe!

While this advice serves as a good start and is arguably more than what most people do, I wanted to dive deeper into the science and determine how sound this advice truly is.

The rationale for this often-cited time frame (28-30 days) is that the entire lifespan of a saltwater ich parasite begins and ends in that 28 day period. This means that parasite is born, finds a host (parasite infects your fish), reproduces, and dies all within that time frame, starting the circle of life all over again.

Most quarantine or treatment protocols advise treatment and observation for a similar period of time in order to declare, the coast is clear.

The theory goes that if you can avoid affecting any fish (eg. leave your fish in quarantine, under treatment for that period of time), you can add them to your tank relatively risk-free.

I am not an expert in infectious fish diseases, (although if I am ever invited to a cocktail party, I may pretend to be one, because it sounds impressive), but I did a fair amount of research to:

- Determine what we truly know about marine ich

- See what scientific evidence was there to support the commonly held beliefs

- De-mystify what we know about marine ich

The best way to protect your saltwater fish tank or reef aquarium is prevention. Prevention means keeping ich-infested fish out of the aquarium. This is done with a quarantine tank. The idea behind quarantine is to isolate a new fish, observe it for several weeks, ideally one month to make sure the fish is healthy. A quarantine aquarium can be as simple as a ten, or twenty-gallon tank with a heater and filter. If it is carrying saltwater ick, a fish will likely show signs during the quarantine. If it does, your quarantine tank helps you keep from infesting your main aquarium and also provides you with a small, safe location to treat your sick fish.

There are several ways to treat ich in a quarantine aquarium, which will be covered in the next few sections.

The water change method to treat saltwater ich

One method involves making 50% water changes every day for two weeks, paying careful attention to being able to siphon off anything lying at the bottom of the tank. This means you must have a bare bottom tank if you have any hope that this is going to work. If you remember back to the third step in the lifecycle (listed above), the protomonts fall to the bottom of the aquarium and become tomonts. The idea here is that since you are vacuuming up the bottom of the tank, each and every day, you should (in theory) be able to remove all of the tomonts/cysts before they become problems.

Of course, since a single parasite can explode into many copies of itself in a short period of time, this method certainly does have an Achilles heel. If you miss even a few, you may not eradicate the problem.

Hyposalinity to treat marine ich

Another non-chemical treatment for saltwater ich is called hyposalinity. One of the forces of chemistry that every aquatic creature must face is called osmotic pressure. Osmotic pressure is the principle behind reverse osmosis water purification in your RO/DI filter (if you have one). You can employ osmosis to your advantage to destroy saltwater ich by lowering the salinity of the water to a level that is close to freshwater (close, but not quite).

Please note that you should only do this with hardy marine fish species, not with any invertebrates at all.

Hyposalinity is one of the most popular ways to treat saltwater ich—because it doesn’t involve any tricky chemicals and because it can be monitored with the same equipment you already have — a hydrometer or refractometer.

I found two separate published methodologies for using hyposalinity to treat saltwater ich:

- A pulsing method

- A constant method

Pulsing method

The pulsing method of marine ich treatment was published by Colorni, in 1987. He recommends diluting the water in your quarantine/hospital tank by 5% every hour down to 10% seawater strength.

Once you reach 10% strength, hold the salinity there for 3 hours and then reverse it back 5% per hour until you return to full-strength seawater.

Repeat this process every three days (dropping to hyposalinity for 3 hours on days 1, 4, 7, 10).

Constant method

In 1996, Noga published a somewhat easier hyposalinity methodology which became a bit more popular and mainstream than the pulsing method. Dr. Noga recommends you reduce salinity from 35 ppt by 5-10 ppt, per day, until you reach a level of 15 ppt salinity. This should take you about 2-4 days.

Once you reach the intended therapeutic level, 15 ppt, he recommends you keep the salinity at that level, by replacing water lost to evaporation, for 21-30 days.

While your fish is in hypo, monitor it for signs of increased stress caused by the change in salinity and stop/reverse the hyposalinity treatment if the fish is under extreme stress.

Once you feel fairly certain you have eradicated all of the ich parasites, slowly increase the salinity to the normal range over a few days to get the fish acclimated to full-strength seawater, before placing it in your main aquarium.

Freshwater dip

The freshwater dip is an old yet effective method against a variety of parasites, including saltwater ich. It is actually a more extreme spin-off of the hyposalinity method. The goal of the freshwater dip is to put the infected fish in complete freshwater for a short period of time (2-5 minutes) to kill off any of the parasites on the outside of the fish.

Fill a bucket with dechlorinated tap water, RO or deionized water. Use a heater to match the temperature to the aquarium. Use a pH buffer to bring the pH to match the aquarium. Be sure to add an air stone to oxygenate the water.

Now add the fish to the bucket for two to five minutes. Some fish show no reaction while others sink to the bottom. There is no reason to panic, this is normal. If you are observing extreme stress, it is probably best to return the infested fish to a quarantine tank and treat the infestation a different way, but if your fish handles the treatment reasonably well, you may be able to kill off enough of the parasite for this method to work.

Some aquarists have found wrasses and firefish to be sensitive to freshwater dips. Use caution and watch the fish and don’t push your luck if your instincts are telling you the fish is not holding up.

Using the transfer method

The transfer method is perhaps one of the oldest and still remains one of the best ways to treat marine ich.

The basic premise with the transfer method is that you move the infected fish to a clean, disinfected tank every few days. After the move, you clean and dry the old tank, removing any cysts and after a few more days, move the fish back to the first tank. When you do this, the parasites that fall off the fish never get a chance to reproduce and reattach to the fish, so after a few cycles of this, once all the parasites fall off and get removed, the fish have been cured.

In 1987, Colorni wrote about this. If you want to use his method of saltwater ich treatment, simply transfer your fish to a clean tank on days 1, 4, 7 and 10, cleaning and drying the alternate tank for at least 24 hours in between uses.

The reason I consider this to still be one of the oldest and best methods for saltwater ich treatment is that even if your fish are infected with a persistent strain of the parasite, like the parasites in the studies that survived as a cyst for 72 days and 5 months, respectively, the saltwater ich will all be removed and either cleaned out or killed during the 24 hours dry period. This mitigates the advantages that even the most persistent strains would have.

Commercial treatments

Three popular commercial treatments for saltwater ich are copper (cupramine), formalin, or chloroquine

These treatments can be challenging because they are toxic to both ich and your sick fish—so you have to be very diligent about following the manufacturer instructions and making sure you do not over-dose the fish. Under-medicating the aquarium carries the separate risk that you won’t even cure the infestation.

So medication can be a bit tricky.

Using copper (copper sulfate) to treat saltwater ich

Using copper to treat a marine ich infection is probably the gold standard method. This is the go-to method that is often described in articles about the topic. According to Noga 1996, the therapeutic dose of copper sulfate is 0.15-.20 mg/L of Cu2+.

It is recommended that you take 2-3 days to reach the therapeutic level, to avoid any unintended toxicity towards the animals you are trying to treat and protect (de Boeck 2003).

Once you achieve the therapeutic dose of copper (0.15-0.20 mg/L), maintain the copper concentration at that level by testing twice a day and adding more copper to maintain the therapeutic level for 3-6 weeks, minimum (Noga 1996).

Copper is notoriously unstable in saltwater

Copper is notoriously unstable in saltwater (an unfortunate characteristic for the ‘gold standard treatment’), which is why it is recommended that you test your copper levels in the morning and the evening with a high-quality test kit. There is a formulation of copper treatment that is more stable in saltwater, called chelated copper (Coppersafe is one tradename), but according to Noga 1996, this type of copper, while more stable in salt water, is a less effective saltwater ich treatment.

Using formalin and hyposalinity

Formalin is an effective agent in treating saltwater ich, especially when combined with hyposalinity. According to Francis-Floyd and Petty 2009, the recommended dosing regimen is 16 ppt hyposalinity and 25 mg/L formalin. You will need to dose 25 mg/L formalin every other day for 4 weeks.

Chloroquine treatment

Chloroquine is a relatively newer chemical treatment for marine ich. The therapeutic dose is 15 mg/L. Unlike some of the other treatments (like copper) which are unstable in saltwater, chloroquine remains active in your saltwater until you remove it with water changes or activated carbon, which makes it a unique marine ich treatment.

The downside of using chloroquine as a saltwater ich treatment is that there are no commercially available tests to help you monitor the levels of chloroquine in your saltwater. You measure once, add it to your tank and hope you got it right.

Combining methods to achieve the greatest chance of success

In Coral magazine, there was an article by Szcebak that highlighted the method used at Roger Williams University. They essentially use copper along with a freshwater dip and the transfer method, in order to be extremely certain they are not introducing parasites into their tanks there. Using different, complementary methods to eliminate parasites makes a lot of sense if you want to control the risks of contamination. The formalin method highlighted here (Francis-Floyd 1996) also combines the use of the chemical formalin with hyposalinity.

What to do if your display tank becomes infested with saltwater ich?

The best way to deal with an ick outbreak is to prevent one from happening, in the first place. The best way to prevent a saltwater ich outbreak from happening is to quarantine new arrivals and use the transfer method to ensure no parasites get in your tank.

If your fish become infected with saltwater ich inside your display tank, here is what you should do:

- Remove all fish to quarantine/hospital tank and treat

- Leave display tank fallow for >5 months to wait out any rogue tomonts

- Consider increasing the temperature a couple of degrees, if you can do this safely, to speed up the saltwater ich lifecycle and increase your chances of eliminating the parasite

- Consider adding biological and UV controls on re-entry (if you didn’t wait the 5 months)

The magic cure for saltwater ich

Haha, that was a dirty trick, for me to use a headline like that, but I regret to inform you that there is no magic cure for saltwater ich fish parasites. So don’t believe the hype, especially if the product claims to be completely reef safe, organic, recycled, or has other slick marketing (and this is coming from a marketer).

I don’t want to bash any products here, but if you have any doubt, I encourage you to try and find out from others in the hobby if the miracle elixirs work. Make sure you ask enough people to get a few data points.

Hopefully, you also noticed that adding cleaner fish species like the Bluestreak cleaner wrasse, neon goby, or even the part-time cleaner Melanurus wrasse, as well as cleaner shrimp species were not listed as cures, either. The fact of the matter is that the cleaners will keep levels lower, because of their predation/feeding, but will not be a cure. And the cleaner fish species are also susceptible to parasites, as well.

Conclusions

My recent research into what has been published about marine ich treatment has expanded my understanding of this tenacious parasite and its ability to survive in our tanks, despite our best efforts. As a result, I’ve shifted my own beliefs away from thinking…28 days of hyposalinity…alone…is enough. It’s not. The research data suggests it is not. Do yourself a favor and figure out an easy way to employ the transfer method and even consider combining methods, like the crew at Roger Williams University does.

Don’t forget about the FREE cheat sheet

I created a chart summary of the methods covered in this post that you can have as a FREE downloadable chart. No strings attached. You don’t even have to sign up for the SaltwaterAquariumBlog Newsletter, even though you’re going to want to. It’s literally just a link to the file I have on my Google Drive. You don’t need to share your info with me, all you need is a Google account to sign in to Google.

here is a link to a free download

For more information

For more information, I recommend you check out these resources:

A few other articles of interest

Please leave a comment below

Am I missing anything? How have you treated marine ich in your aquarium? Please leave a comment below, I want to hear from you!

Leave a Reply