The dangers of palytoxin and why you need to read this article

Palytoxin is one of the most toxic marine chemicals and it might be in your home right now.

I hope that caught your attention.

One way to determine how toxic a chemical is is to give it to a lab mouse and see what happens. 6 grams of palytoxin would be enough to kill 1 billion mice.

While that would be tragic, it’s not the mice I’m most worried about–it’s my family and your family.

At the prompting of a concerned friend of mine, I set out to research this topic and attempt to raise awareness of the risks and shine a light on the need for a better understanding of the impact of this toxin in our hobby.

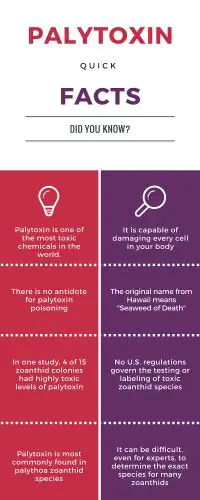

Did you know? Palytoxin Quick Facts

- Palytoxin is one of the most toxic poisons in the world

- Capable of damaging every cell in your body

- Can cause tissue damage, a decrease in respiratory function, coma or death

- Discovered in Hawaii, the name limu-make-o-Hana, literally means “seaweed of death from Hana”

- According to the CDC there is no antidote

- No U.S. regulations govern the testing or labeling of coral that might contain toxins, including palytoxin

- A study in 2011 found that 4 out of 15 zoanthid colonies had highly toxic levels of palytoxin

Image source: Deeds article

What makes palytoxin so toxic?

Palytoxin destroys a basic functionality that every cell in your body needs–which means it will damage any cell in your body that it comes into contact with.

On a cellular level, palytoxin binds with the sodium pump and destroys the ion gradient every cell needs to function properly, and apparently, a little bit goes a long way.

The most common complication of palytoxin poisoning (according to Wikipedia) is the rapid destruction of muscle tissue, called rhabdomyolysis. To put it in a more gory context, the guts of your muscle cells just leak out (and are permanently damaged). I’m sure you can see how this is a really bad thing if it starts to affect your brain, nervous system, heart tissue, or any other part of your body that you hold dear or which you depend on to stay alive.

What are the symptoms of palytoxin poisoning?

If you physically come into contact with palytoxin–on your hands or in your eye, you would potentially feel a tingling or burning sensation and ultimately see damage to the area that came into contact with it–as the palytoxin binds with the cells in that area and destroys them.

But palytoxin poisoning doesn’t always happen because you handled a palythoa coral with your bare hands. There are reports of palytoxin poisoning from aerosols–which means that the palytoxin somehow got into the air and made people sick.

Other symptoms of palytoxin exposure include burning/tingling in your mouth or throat, a metallic taste, nausea, vomiting, muscle spasms, loss of muscle coordination, difficulty breathing, headache, scratchy throat, joint/muscle pain, fevers, tremors, kidney pain and more.

I don’t mean for this to sound like one of those pharmaceutical commercials with the laundry list of side effects. But I hope this gives you some symptoms to look for.

For more information about the symptoms, check out the comprehensive list of symptoms from the CDC report here.

Real-life cases about people who suffered from palytoxin

The most famous (or is the right word notorious) situation I can recall was from an individual who was cooking their live rock to get rid of some unwanted palythoa hitchhikers.

“Cooking live rock” was a term that was used to describe the process of letting uncured live rock cure in a vessel before being added to a display tank. Unfortunately for that hobbyist and his family, he didn’t understand that you didn’t actually cook the live rock–a dangerous misunderstanding.

Boiling the live rock released palytoxin into the air–which made the family all very, very sick. It almost killed them.

You may be thinking, “Thanks for telling me that, Al, I’ll make sure not to cook my corals and I’ll be just fine.”

Not so fast.

In 2014, an entire family suffered palytoxin poisoning from a coral colony 7 hours after adding a colony to their tank. This is not some flim-flam story on an online forum from some unknown author–this was published by the CDC. The palytoxin was in the air–and they weren’t cooking their live rocks on the stove.

In 2015, there was a case reported about a hobbyist who required emergency treatment after rinsing off a piece of live rock in his sink.

The scariest thought is that…if I passed out because of palytoxin poisoning while working on my tank–would my wife or the local medical staff know enough to even suspect palytoxin poisoning?

I wonder how many cases of mild effects from palytoxin go unreported every year–simply because we don’t know it was palytoxin.

One other case was confused with Pulsing Xenia, which is not a palytoxin-producing coral species. Learn more about that here.

Which zoanthids contain palytoxin?

One of the most common questions I get is this–what zoanthids contain palytoxin?

The answer:

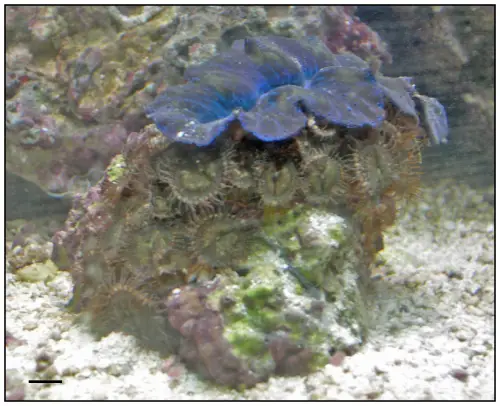

The zoanthid species that are thought to contain the most palytoxin are the palythoa zoanthids, specifically the most toxic zoanthid species is thought to be Palythoa toxica–but as you may already be aware, it can be challenging even for experienced scientists to know the exact species of a zoanthid.

In one of the reports, cataloged here:

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0018235

They treated a patient who was poisoned, performed histological work, after the fact, to determine what zoanthid species it was–and were unable to confirm what species it was.

Let me say that again (a different way). Even when there was a confirmed case of poisoning–and scientists tried to determine what species was in the tank–the best they could do was figure out that it was some sort of Palythoa.

In that same study–scientists bought every type of distinct zoanthid they could find across 3 local fish stores and ended up with 15 distinct colonies. They found highly toxic levels of palytoxin in 4 of the 15 colonies!

According to an article on TFH

“Since palytoxin was discovered in Hawai‘i, it has also been found in other species, such as P. tuberculosa near Ishigaki Island in the Ryukyus of Japan, and P. caribaeorum and P. mammilosa in Jamaica and the Bahamas (Moore and Scheuer, 1971). It was also isolated in P. vestitus from Hawai‘i, and other unidentified species in Tahiti—even sea anemones, crabs, and a dinoflagellate (one-celled organism) (Oku, 2004). The toxin is no longer as isolated as originally thought, and to make matters worse, most zoanthid specimens can be difficult to identify on the species or even genus levels.”

Call to action

It seems to me that there is plenty of room for us, as a hobby, to collectively improve the way we approach palytoxin. I can think of at least 5 ways we can improve.

- Clear identification of species known to carry palytoxin

- Warning label and information when Zoanthids are purchased

- Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater–or throw out the purple people eaters with the water change water

- Better education about how to protect yourself

- Better communication with family members

Clear identification of species known to carry palytoxin

We need a better way to identify what species carry palytoxin. It shouldn’t be a mystery, and you shouldn’t have to read this blog to find out about it.

Warning label and safety information

Cigarettes and alcohol may cause slow damage to your body over time and with chronic use and they carry major warnings on them. Palytoxin could kill or injure you or your family. There should be a warning label and safety information provided when palytoxin-containing zoanthids are purchased.

Now, I know there is a cost to that–but you deserve to know that your coral could kill you in your sleep before you purchase it?

Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater

I’m not recommending a witch hunt here for zoanthids. I’m just advocating for some common sense, maybe some caution and transparency about the risks. That doesn’t mean you should ditch the hundreds of dollars of coral frags or send angry letters to me or your local fish store.

Better education about how to protect yourself

I don’t think there is very much known about the best ways to protect yourself from the dangers of palytoxin in your home aquarium. The standard advice I’ve seen is to use gloves, goggles, and wash your hands–which is probably good advice–but I don’t think it is comprehensive enough.

Personal protective equipment

According to the CDC, there is no evidence-based recommendation for personal protective equipment–which means there haven’t been any studies to help us definitively demonstrate what works and doesn’t work–and which means that any advice, including the advice contained here, is well-intended, but just a guess.

Some of the reports describe people becoming injured when the palytoxin was absorbed into their body through the skin, so it seems to make perfectly good sense to always wear gloves when you have your hands in your tank.

Aerosols are probably the biggest danger

Use caution whenever you are engaging in an activity that could cause the palytoxin to get into the air–scrubbing live rock or using moving water.

People have gotten sick just from being in the house after the corals were added to the home aquarium–which suggests no amount of personal protective equipment would help. Technically, I suppose, a respirator would help–but who wants to wear a respirator when they get home–if it’s in the air–and it’s toxic–that’s bad.

Decontamination of equipment

To neutralize palytoxin that might be on your equipment (your gloves, specimen containers, tongs or buckets), the CDC recommends the following:

“Palytoxin can be neutralized by soaking the coral for 30 minutes in a ≥0.1% household bleach solution (1 part 5%–6% sodium hypochlorite [household bleach] to 10 parts water, prepared fresh). Contaminated items should be soaked in diluted bleach before disposal.”

I don’t think I have ever decontaminated my equipment after using it, but now that I’ve researched this topic and written about it, I’m a big advocate for decontamination.

I’ll add to the CDC recommendation here that if you intend to use that equipment in your tank again, rinse it in a bucket with a de-chlorinator before using it in your tank again. They’re focused on decontamination, but we have to make sure you don’t hurt your tank.

Better communication with family members

Talking to a spouse or loved one about the potential perils of palytoxin may sound like a recipe that ensures your tank gets listed for sale on Craigslist that evening, but I do think it makes good sense to talk with them about the risks of palytoxin–at least those who are old enough to understand the implications and be mindful. Share the list of symptoms with them and let them know about it–so that they can communicate with healthcare providers on your behalf, in the event you get injured. I know that’s a bit morbid.

In the Reef Journal, I dedicated a page for writing down any risks in your tank for a similar purpose–to help the non-reefers in the family understand and or communicate potential problems if needed. You don’t need a Reef Journal to do that, but I recommend you make a list and review it with your loved ones.

What to do if you think you might be affected by palytoxin exposure

This is not medical advice, I don’t recommend taking medical advice from dorks with websites and the conspicuous absence of a medical degree. If you think you might be experiencing any of those symptoms, you should get that checked out, ASAP, but a healthcare provider–you know–the kind with medical degrees. There isn’t much known about palytoxin poisoning–and there certainly isn’t much about it in the medical literature–so you may need to educate them a bit.

For more information

If you want to dig a little deeper into the world of palytoxin, here are some resources I used to draw my own conclusions and for you to review and make your own conclusions:

Article on Tropical Fish Hobbyist

Medical cases and papers

- CDC case summary of palytoxin inhalation exposures affecting 10 different people

- You can read the abstracts (brief summary) for free. To get the full articles, you may need to visit a library.

- A case involving injury through the skin and a similar case

- Wikipedia

An Expert perspective on palythoa

Looking for an alternative to Zoanthids? Check out these other colorful corals

Zoanthid gardens are super popular because of their psychedelic colors. But as we’ve already established, they do come with some risks. As an alternative, check out some of these other amazing and colorful coral types:

- Ricordea and other Mushroom Corals

- Plate Corals

- Scolymia

- Blastomussa

If you want to continue your journey, check out The Reef Aquarium Series of books: The New Saltwater Aquarium Guide, How to Frag Corals, 107 Tips for the Marine Reef Aquarium, and the Reef Journal.

Follow me on Facebook

Leave a Reply